First printed in the Folk Harp Journal Spring 2003

The Annual Festival of Harps which has become a San Francisco Bay Area institution, has since 1989, been host to every possible manifestation of harp, harp player, and harp tradition. Festival goers have been treated to harp music from five continents and three millennia. The Festival’s popularity is such that in the year 1999, to celebrate the Festival’s first decade, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown declared November 14th to be “Festival of Harps Day.” It has been celebrated as such ever since, with free public concerts and other harp-related events.

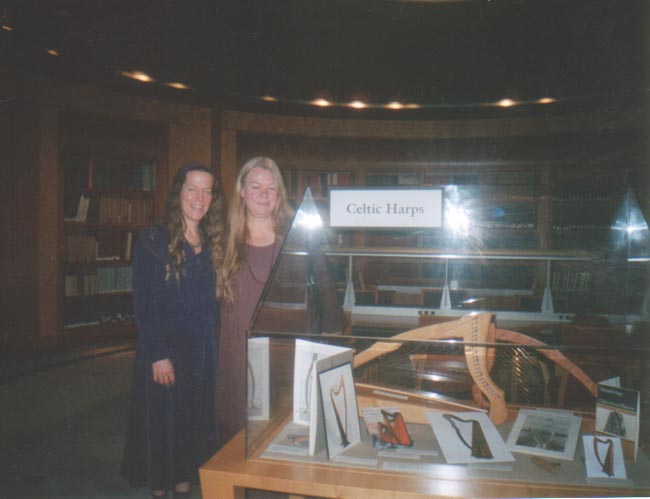

Curator, Diana Stork and Ann Heymann at the opening of the exhibit, standing beside the Celtic Harp Floor case displayOne such event has been a lecture-performance at the San Francisco Main Library, entitled “History of the Harp.” This presentation was developed by FOH Director Diana Stork and her musician husband, Dr. Teed Rockwell, the President of the Multi-Cultural Music Fellowship, which produces FOH, and other musical events. This year, Diana and MCMF were honored by a request from library curator Everett Erlandson to create a “History of the Harp” exhibit. The exhibit opened in mid-November 2002, dovetailing nicely with the opening of FOH. This was great for Festival goers and harp fans in general, but it presented a potential logistical nightmare for Diana, already consumed by FOH matters. She had less than 2 months to get the exhibit organized and ready to open.

Fortunately, a call for help brought in expert and generous assistance from every corner of the harp world, and MCMF was able to find all the help needed to get the exhibit in place. Contributors included harpists, harp scholars and ethnomusicologists, among them many names familiar to FOH fans. As Diana remarked, “Only a small part of the harp’s 5,000 year history could be presented” and certain choices had to be made. The exhibit expands on the topics in Stork and Rockwell’s “History of the Harp” performance, including Prehistoric, African, Asian, Celtic, Latin American, and Western European (designated as “Historical Harps”); the harp in literature and media; harp-making; and a segment on “New Directions for the Harp.” Each contributor assembled as many notes, photographs, and actual harps as the space would allow.

One of several floor cases. This one contained info on harps in literature and film.

One of several floor cases. This one contained info on harps in literature and film.

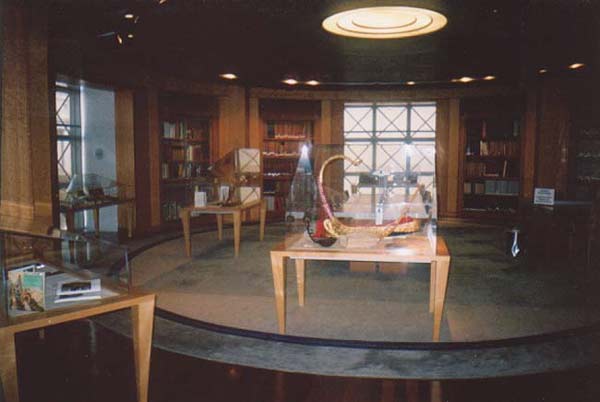

One only wishes that a bit more space might have been allowed. The exhibit is housed on the fourth floor of the library—the Music and Performing Arts section – in and just outside the Steve Silver Beach Blanket Babylon Room (donated by the founder of yet another San Francisco musical tradition). The graceful round room makes a fine setting for the exhibit. The rather small size of the floor cases makes it impossible to display the spectacular larger harps, but the exhibit makes up in aesthetic appeal for what it lacks in drama.

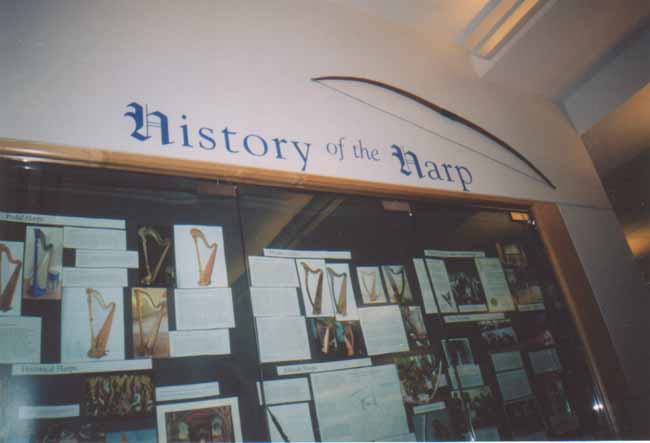

Outside the room’s entrance is a wall case featuring sections on each of the categories covered. The amount of information and number of visual images of the harp contained in this one case is astonishing, and provides a very visceral sense of the length and breadth of the instrument’s history and influence. Over this case hangs a hunting bow, an image as ancient and archetypal as the harp itself. The bow is thought to be the origin and ancestor of the harp.

A stunning crimson and gold Burmese bow-harp draws your eye immediately to the central floor case as you enter the exhibit room. Bow-harps, common to Asia and Africa, have a sound-box and a harmonic curve to which the strings are attached, but are missing the fore-pillar of the familiar European harp. Perhaps the most surprising information in the exhibit relates to harps in Africa and Asia. Not only do they exist there, they have enjoyed great importance and prevalence. In Africa there is an area known to music scholars as the harp zone, extending across sub-Saharan Africa from the east to the west coast. Nearly 150 different African peoples use the harp, and three different types of harp are common. Best known to Westerners is the African bow-harp known as the adungu. James Makubuya, a scholar and master of the adungu, designed the African harps exhibit.

Rudiger Opperman, harpist and harp builder, who has spent many years researching non-Western harp music, contributed “Harps in Asia.” The Asian harp seems to have originated—again, in the form of a bow-harp—in Central Asia and spread to every direction, carried by the Scyths, the Mongols, the Turks, and other Asian nomads to every corner of the continent. Many forms of the Asian harp, sadly, have died out, remaining only in art and in literature. In China the harp has survived in two forms, a horizontal form similar to a koto (the Japanese horizontal harp), and a bow-harp. China’s history demonstrates how political factors contribute to the demise or popularity of an instrument: the Maoist government condemned the horizontal harp and persecuted its players because of the harp’s connection with Confucian and Taoist ideals. The bow-harp, on the other hand, won their full approval and support. One of the Asian harp section photographs shows a Chinese harp master, Cui Junzhi, playing a harp of her own design which incorporates features of both types of harp. He does not mention whether the People’s Republic has approved this hybrid, but Cui Junzhi now lives in Northern California.

Main View of the room with various floor cases. A lovely red Burmese harp greets visitors.Celtic harpists Mitch Landy and Maureen Brennan contributed the materials for the contemporary Celtic harp display, including small harps. Ann Heymann, one of the few masters of the traditional Irish wire-strung harp provided the ancient Celtic harp segment. Heymann’s notes, clearly exhaustively researched, are fascinating, includes a glowing review of Irish harp technique from a twelfth century music critic as well as an ancient Irish legend tracing the origin of the harp to a disillusioned housewife and a beached whale. The ancient Celtic harp design and playing techniques were sharply different from those favored today, and here again, politics played a role. In Ireland, under a suppressive English rule that lasted five centuries, harp players were rightly perceived as Irish nationalists and the harp itself as a symbol of Irish freedom. Queen Elizabeth I ordered succinctly, “Hang the harpers and burn the harps,” with the eventual result that harp playing, once essential to Irish culture, died out altogether. Both Celtic harps and harping have had to be almost entirely reinvented, and much of this has been done in the years since the 1970’s. Landy’s exhibit deals chiefly with new Celtic harp design and the playing of musicians of this latest harp renaissance.

Dr. Cheryl Ann Fulton traced the harp’s development in Western Europe from medieval to nearly-modern times, with special attention to the Welsh triple-strung harp, of which she is one of only a handful of masters living today. Dr. Fulton’s presentation was especially lavish in photographs, including many of paintings depicting the harp, often drawn from Biblical themes. Harpist Laura Simpson provided a history of the development of the double-action pedal harp, changes which moved the harp into its place in the orchestra but contributed to the temporary demise of the diatonic harp. Fortunately, the classical and the folk harp are at last learning to live together.

The European baroque harp tradition, according to Latin musicologist Allegrah Hardulfi, was the ancestor of a wholly different descendant: the harp music of Latin America. Among the Spanish immigrants to Latin America were musicians who brought with them their large, light-bodied harps. The Spanish were amazed at how quickly the native population adopted the harp. Combining the European method of playing with their own musical traditions, they created not one but many new styles, varying greatly from country to country. The harp has become integral to the folk music of Mexico, Venezuela and Peru, to give only a few examples.

Of particular interest was Teed Rockwell’s segment on “New Directions for the Harp.” In the new harp music we find combined every element of both traditional and contemporary music. Stork and Rockwell’s own group Geist has drawn upon the harp’s African, Celtic, Asian and Latin roots in their original compositions, combining them with jazz, rock, funk, country, and Indian ragas, while juxtaposing the folk harp with the electronic Chapman stick. Europe’s Andreas Vollenweider and Rudiger Oppermann, as well as America’s Sarah Voynow, have created astonishing new sounds by altering harp construction and stringing, and adding electric amplification and sound modification. Park Stickney, a jazz harpist who has been known to transport his harp in the sidecar of a motorcycle, has created pedal techniques that let him play jazz chords and progressions which had formerly been thought impossible to play on a classical harp. The answer to the question, “What direction is the harp heading in these days?” seems to be, “Anywhere it wants to.” There does not seem to be a border the harp can’t cross in the hands of an innovative player.

Materials on harp-making came from William Rees and from Lyon and Healy, some of the best-known harp makers in the world. They have shown their versatility and love for the harp by keeping up with the times, developing diatonic and electrically amplified harps in response to the demands of the new generation of harp players.

Much of this information, of course, will already be familiar to readers of the Folk Harp Journal. To many other people, the harp brings to mind images of the quaint, the sentimental or the archaic. The value of this exhibit is its ability to reach a great many people with the news that the harp is vibrantly alive all over the world, speaking new languages and taking new forms. It’s hard to imagine anyone seeing this exhibit without wanting to go out and hear some harp music.